Hydrogen fuel cells have traditionally chased battery-electric vehicle technology as a zero-emission fuel solution. With acceptance now increasing, APTI discovers that fuel cell technology offers many benefits to push forward the decarbonization revolution.

Hydrogen may be the most plentiful chemical element in nature, but it has yet to gain ground on battery-electric technology in the race for decarbonization. “Compared with batteries, hydrogen is a relatively inefficient energy carrier. This is the main argument against its use in transportation,” says Darren Davies, CEO and technical director at simulation and advanced engineering specialist D2H Advanced Technologies.

Comparing FCEV technology with pure battery-electric systems largely comes down to the energy density of the complete system, explains Richard Gordon, head of research and development, automotive and industrial at Ricardo. “In vehicles where the mass and volume of what is being transported is critical, the large mass and volume of a battery solution becomes a disadvantage.” BEV technology will likely dominate for lighter vehicle applications; FCEV’s current focus is on the hard-to-decarbonize heavy-duty trucks (HDT) sector. “A high-pressure gas storage and fuel cell system for a truck application typically has significantly less mass and occupies less volume than a battery solution, leaving more vital payload capacity,” explains Gordon. “We are trying to understand – through the ZEFES (zero-emission, flexible vehicle platforms with modular powertrains serving the long-haul freight ecosystem) program, co-funded by the European Commission – how FCEV trucks can be deployed, and what information fleets need to make decisions around adopting a new powertrain technology,” he continues.

Smart solution

However, an FCEV need has also emerged in the lighter-duty BEV sector, where recharging can be problematic, reports Steve Gill, CEO, automotive at First Hydrogen. “Our customers who don’t necessarily need a lot of range or payload are struggling with how they recharge their vehicles and are looking for alternatives,” he says. Fast, easy and safe refueling with no compromise on payload and cargo volume are two reasons why Stellantis developed a plug-in FCEV van, based on a mid-size BEV LCV platform sold by three of the group’s brands.

Development spanned four years, and the FCEV uses a 45kW fuel cell supplied by Symbio, three storage tanks with a 4.4kg capacity – located under the floor where the larger battery is in the BEV model – and a 10.5kWh lithium-ion battery. EU WLTP-certified range is up to 400km. “FCEV, in addition to BEV, is a smart solution to decarbonize transportation,” confirms Jean-Michel Billig, Stellantis’s chief technology officer for hydrogen fuel cell development. “By introducing FCEV on LCV and HDT fleets, we could realize the take-off of the technology and refueling solutions,” he says.

First Hydrogen also has an LCV focus. “We’ve developed two vehicles based on Man eTGEs working with AVL and Ballard, because AVL is a leading company in powertrain engineering and Ballard is a fuel cell technology leader,” says Gill.

The vans will soon undergo UK trials that will influence First Hydrogen’s next generation of FCEVs. The vehicles use a mix of off-the-shelf and more bespoke components, Gill explains. “It’s necessary to use common components to access scale, but components aren’t really differentiators. The Ballard fuel cell is not off-the-shelf. It’s the latest FC technology that we’ve gone into early in its development phase.”

Toyota has long been a believer in hydrogen, and Jon Hunt, manager of alternative fuels, says it considers FCEVs the ultimate environmentally friendly solution for sustainable mobility. “On the technical side, there is the way they work, with zero- emission, quiet, smooth and powerful operation, as well as the practicalities of relatively low weight, durability, low long-term cost, material use, reuse and recycling capability,” he says, believing that the speed of refueling and the long duty cycles make fuel cells additionally attractive.

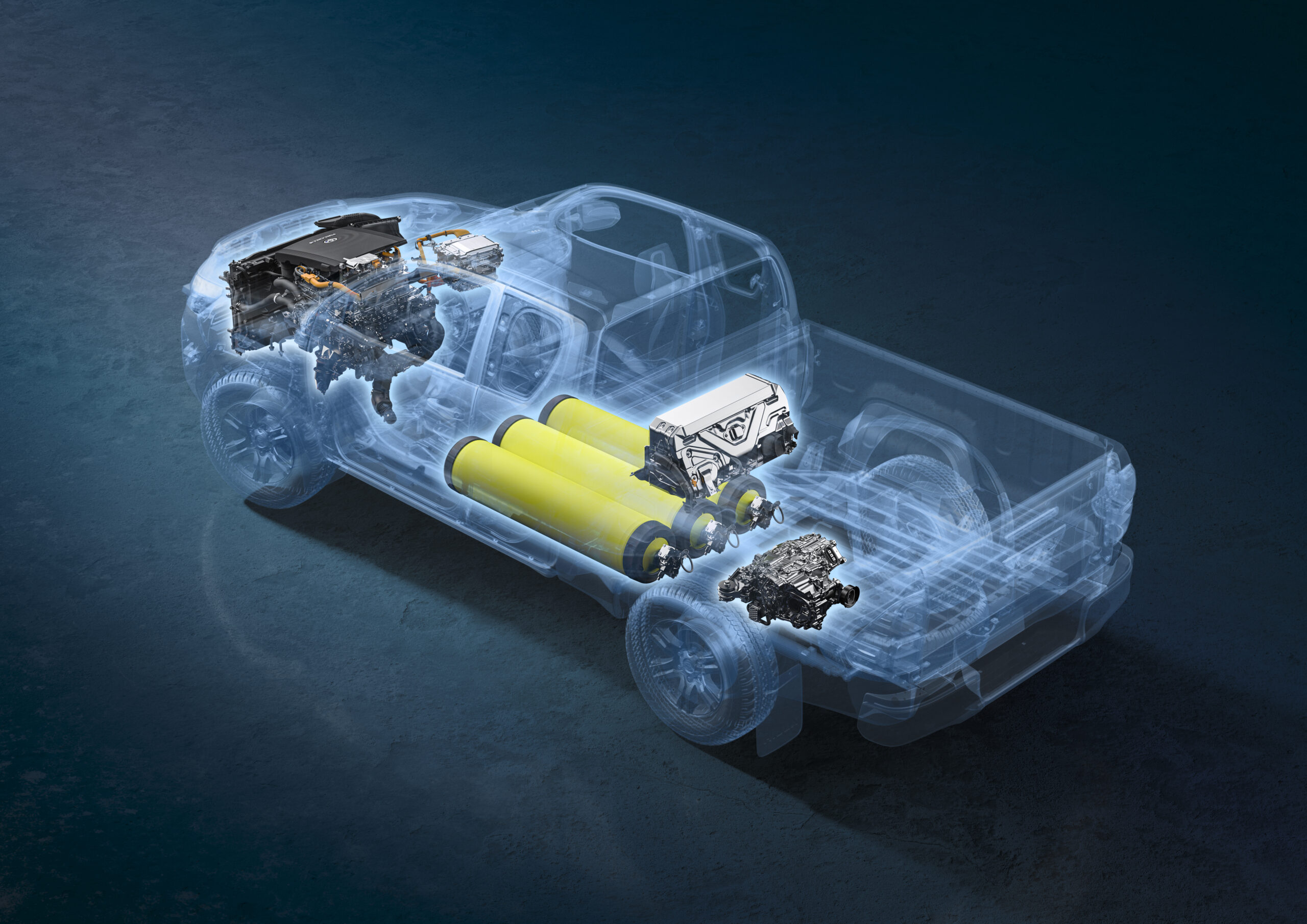

A leading proponent in the passenger car FCEV sector with the Mirai, Toyota is leading a consortium to develop an FCEV-powered prototype of its Hilux pickup. Toyota Motor Manufacturing (UK) Ltd (TMUK) has secured UK government funding for the project through the Advanced Propulsion Centre and consortium members include D2H and Ricardo, European Thermodynamics and Thatcham Research.

Why a pickup? “Hydrogen and fuel cell applications are applicable across all sectors and the technology is available but there are greater benefits in certain sectors where few alternatives exist,” says Hunt. “For Toyota, the launch in passenger cars, where use can be scaled quickly, is an ideal way to build understanding and prove the technical viability. The next stage is to address the most-difficult-to-decarbonize sectors in the most challenging environments – a pickup is ideal to test the technology in extreme conditions,” he explains.

The project will share some components from Toyota’s second-generation fuel cell system. Initial prototypes will be produced at TMUK’s Burnaston production site in 2023, with the intention of small series production. D2H will use its expertise in simulation, aerodynamics and thermodynamics to address the challenges involved in developing cooling systems and airflow strategies that deliver maximum efficiency. “FCEV supports work environments or locations that lack developed charging infrastructure, or require limited vehicle downtime because vehicles can be refueled quickly and easily from hydrogen stored on-site,” says Davies.

Standardization and innovation

Standardization of interfaces and materials, testing and validation approaches, growing supply chain availability and the sharing of systems across multiple applications can bring the considerable FCEV implementation costs down. “Anything that increases the manufacturing volume and eases platform integration tasks helps,” Gordon explains, believing innovation in simplification is equally important. “Fuel cell operation is highly complex, requiring the perfect orchestration of interacting fluid flows to ensure stack life and performance. One example is the use of external humidifiers to maintain the ion conductivity of the fuel cell membrane. These, along with electric air compressors, are bulky devices that can be difficult to package.”

Further innovations to increase PEM fuel cell operating temperatures are also crucial. “Half of the fuel cell generated energy is lost to the coolant. The radiators of FCEVs tend to be very large to dissipate heat over a wide range of ambient temperatures. If the fuel cell can operate at higher temperatures (over 90°C), radiator surface area can be reduced, significantly easing the integration challenge,” says Gordon.

As with other industries, scale is important and will help to substantially reduce costs. “By using a common platform, maximizing carry-over and developing modularity, development costs are already quite similar at vehicle level,” explains Billig. “Innovation could help to reduce future cost; increasing the maximum temperature and efficiency of the stack will decrease cooling requirements,” he says.

Bramble Energy’s printed circuit board fuel cell (PCBFC) range-extending technology – featuring a proton exchange membrane fuel cell within a printed circuit board – is looking to leverage the existing PCB supply chain to scale up fuel cell production through its simpler design and manufacturing process and its lower material cost. Freed from the constraints of an existing body shape, designing a vehicle around a fuel cell also offers scope for further efficiencies, according to Davies. “There’s much more to come if a vehicle is designed specifically for fuel cells, rather than try to put them into something that exists already,” he explains. “Development of fuel cells will really be based around them rather than putting them into existing vehicles.”

A wider FCEV ecosystem is also an essential part of the transition needed for fuel cells to play a greater zero-emission fuel role. “An ecosystem has to be considered,” Billig states. “To offer sustainable mobility solutions (lifecycle assessment methodology) we need to have green H2, infrastructure and efficient vehicles, as well as control raw material and recyclability.” Infrastructure is still a major sticking point, but improvements are on the horizon. “There are 30 or so global governments that have put together hydrogen plans, many across industries, not just transport,” says Gill, adding, “Europe has accelerated its plans since the start of the Ukraine war, aiming to have a refueling station every 100km by 2027. The US has also introduced its Inflation Reduction Act, which invests US$369bn into clean tech, with a focus on hydrogen.”

Investment from major OEMs and suppliers also helps drive scale, therefore reducing costs. “Some of the big European suppliers such as Bosch, Faurecia and ElringKlinger are making serious investments into fuel cell and hydrogen technology,” Gill confirms.

At a UK local level, the Tees Valley Hydrogen Innovation Project supports the development of a local hydrogen economy. “The objective is to produce a replicable model that can be taken to Bristol or to Manchester,” explains Allan Rushforth, chief commercial officer of the automotive division at First Hydrogen.

Regional or national networks could crack the infrastructure ‘chicken and egg’ phase, led by the use of heavy-duty transportation, says Gill. “The opportunity is heavy duty, as it provides the volume of fuel needed by the fuel suppliers. The heavy-duty consumption per vehicle supplies that volume from which others can feed.”

Echoing that trend, a large network based around the main road transportation arteries of Europe supplying hydrogen for heavy duty is planned, enabling other users to network off it.

The generation of green hydrogen – electrolysis hydrogen production using renewable sources – is costly due to the technology involved, and on-site production of hydrogen fuel is only really feasible at massive scale. “In big markets like Germany or the US, there may be a case for electrolysis on-site where the economics of transporting hydrogen a long way don’t work. You can get scale on major arterial roads,” says Rushforth.

Mixed ecosystem

Davies believes the future will see a blend of FCEV and BEV technologies. “It is likely a mix of FCEV and BEV solutions will be used for future transportation requirements,” he says, adding, “FCEV technology has the potential to deliver across all sectors.” Gordon also points to a BEV and FCEV co-existent future; battery raw material availability is at a premium and some applications are impossible to battery electrify. “A range of power storage and conversion technologies will exist side by side, optimized for each application,” he says.

Following the arrival of BEVs, Davies believes the benefits of hydrogen are smaller leaps for people to understand.

“Hydrogen will become a very significant factor in the fueling of all transportation,” he asserts. “Its potential reach is so much higher, providing a solution where batteries simply cannot.”

Cooling challenge

Fuel cell technology still has development challenges to overcome. D2H’s Darren Davies reports that all FCEVs require more cooling than BEVs as the fuel cell generates waste heat. “The challenge is to maximize cooling performance within the overall vehicle requirements,” he says. “This means using the least amount of air for fuel cell cooling (to reduce aerodynamic drag) and packaging the cooling solutions within essential structural and safety systems.” This has seen older practices return. “Traditional engineering challenges are becoming more important, such as weight, drag saving and improving cooling,” says Davies. “When you’re not getting as much energy from hydrogen for the work to get it to the vehicle, making vehicles lighter, more aerodynamic and with more efficient cooling systems becomes more important.”

The fuel cell stack itself is the subject of intense development, from supporting materials and structures to the electrochemistry and catalyst materials and manufacturing technique optimization. “This is focused on improving life expectancy and power density, reducing costs and improving overall system efficiency, such as PEM stacks operating at higher temperatures,” says Gordon.

“The fuel cell cost, performance, materials use and durability can all be improved,” agrees Hunt. “The associated power electronics and electrical powertrains, including battery technology, also need further development.”

Other FCEV challenges include hydrogen fuel storage. “Gaseous 350 and 700 bar systems are available, but they are still expensive and heavy (~4% H2 weight to storage system weight) and a challenge to recycle,” says Gordon. “Liquid storage can offer improved gravimetric and volumetric efficiencies at the expense of energy efficiency (liquefaction of the hydrogen) and boil-off management. But there are now improved tank materials and designs, metal hydride storage studies and novel vehicle integration approaches.”